Make Sourdough Bread Extra Tangy! Sour Sourdough Guide

Making sourdough bread taste more sour is such a well-versed topic. I could have written a book with the recommendations I’ve seen!

Some of these theories work, but many aren’t supported by science.

I’ve whittled the good ideas down so you’ll know what makes sourdough sour and how you can change the type of acidic flavour in your sourdough.

What Makes Sourdough Sour?

A sourdough starter is a culture of wild yeast and acid bacteria strains captured from the local environment or contained within the flour.

When combined with moist flour, the yeast and acid bacteria ferment to produce CO2 gas (alongside other compounds) to make bread rise.

Several fermentation routes occur in sourdough, and thousands of species and combinations of yeast and bacteria can be found in a starter.

These collections create the unique behaviours, tastes and smells in your sourdough.

Lactic Acid Bacteria (LAB) and wild yeasts multiply in the starter as it matures.

They respire and ferment to produce carbon dioxide, which makes the starter rise.

After regular feedings of fresh flour and water, a mature starter develops.

How a starter produces acid

Flour is full of starch. Acid bacteria and cultured yeasts work together to supply enzymes that break down starch into sugar, and then into simpler hexose sugars.

The simple sugars will be consumed by the LAB or yeast cells through various pathways to produce:

- Carbon dioxide

- Ethanol alcohol

- Acetic acid

- Lactic acid

- Water

- Other various organic compounds

These products provide flavour and aroma, but fermentation routes producing acetic and lactic acid are what make bread taste sour.

In a moment, I’ll share several tips to make your sourdough bread taste more sour.

Most focus on producing more organic acids (acetic and lactic).

The Benefits Of Making Extra Sour Sourdough Bread

Not all sourdough bread has to be sour. Plenty of bakers (and eaters!) prefer their sourdough lightly flavoured.

But there are some benefits of lowering the pH of sourdough bread to make it taste extra tangy:

- Health benefits- slows sugar absorption, more minerals absorbed, improves digestive organs

- Bread remains fresher for longer

- Mould growth is resited

- Acids cause clumping in the bread crumb – leading to an irregular, open crumb structure

- The production of acetic acids releases carbon dioxide, leading to a faster rise.

Yet there are downsides to acidic sourdough!

Lactic acids break down gluten strands into individual amino acids, weakening the dough structure. A well-fermented dough is challenging to handle and has a higher risk of collapsing during proofing or baking.

How To Make Your Sourdough Starter More Sour

The most crucial factor in making your bread sour is having a sour sourdough starter.

As bread dough contains salt, it inhibits the growth of bacteria.

So, if you want sour bread, you must have a fully active and sour starter.

These following points explain how to do this:

Use flour with a high ash content

The ash content of the flour is found by burning it —the more products left after burning (the ash), the higher the ash content.

Protein, bran, and wheat germ are the main products that contribute to ash content.

A higher ratio of these products in the flour means more minerals and bacteria for a starter to process.

Flours high in minerals and bacteria provide more matter to consume, so when used in a sourdough starter, they take longer to rise. This produces a robust starter that is more acidic.

White flour that has been finely sifted (such as Italian 00 flour) is whiter and has a lower ash content.

Rye flour has a high concentration of minerals, proteins and starches, such as pentosans, which are slow to break down.

Bread flour (though not as complex as whole grain flour), has a higher ash content than all-purpose flour, provided by the extra protein in the wheat.

High-quality bread flour can rise for longer and make a sourer starter or bread.

Organic flour contains more bacteria due to the lighter cleaning products used.

Stoneground flour contains a higher ash content than modern roller-milled wheat.

Which flour is best for a sour starter?

Choosing a flour that can enjoy a long rise and has plenty of bacteria to cultivate is essential for an active sour starter.

The ideal flour combination is 80% organic white bread flour with 20% organic dark rye.

For a wholemeal starter, you can use 100% whole wheat or a split of 50% whole wheat, 40% white bread flour, and 10% dark rye.

Feed your starter when it peaks

Once the starter hits the summit of its rise, it will stay at its peak for an hour or two, sometimes longer, depending on the temperature and the flour used.

At this point, the LAB microflora population continue to increase. This prevents the multiplication of yeast cells and gas production as it becomes more acidic and alcoholic. LAB continues to multiply.

A perfect time to feed your starter is just before it collapses. Do this for 3-4 feeds, and you will quickly notice more sour notes in your starter.

Starve your starter (occasionally)

If you wait too long before feeding your starter, it will collapse.

Doing this increases the acidic bacteria but does weaken the levain.

If this happens as a one-off, your starter will be strong enough to cope, and the extra acidic bacteria it produces will enhance its sourness.

I don’t recommend doing this often as the gluten will be damaged and won’t pass structural maturity to the dough.

TIP: Separate your starter into several jars and make different changes to each! This way, you can choose which one is your favourite!

Keep your starter temperature consistent

In keeping a sourdough starter, you are cultivating bacteria and fungi.

For it to be at optimum vibrancy, it must be kept at a temperature where the bacteria is most active.

Both yeast and bacteria are quicker to operate when warm, but if your starter is too warm, the enzymes necessary for breaking down starch are less active.

The ideal temperature to keep your starter is between 20-35C (68-100F).

Strains of bacteria and yeasts are more active at different temperatures.

Therefore, fluctuations in temperature upset the culture’s balance, so it’s best to store your starter at a constant temperature. Introducing The Sourdough Home:

The Sourdough Home – Starter Proofer

For the ultimate starter, you need to keep it at a constant temperature. And with Brod and Taylor’s Starter Home, you can do just this!!

Create a more robust starter, experiment with different flavours and never worry about feeding times again! The Starter Home is the perfect product for any serious sourdough baker!

Keeping the temperature warm and consistent is a game-changer in achieving sourdough supremacy!

Incorporate oxygen into your starter

Acid bacteria multiply in the presence of oxygen.

To add oxygen to your starter, you can give it an aerated stir when refreshing. Another option is to leave the lid on your jar slightly loose (don’t loosen it completely, as it will dry out and attract insects).

Liquid vs stiff starter

The sour taste of sourdough bread comes from lactic and acetic acids, which are produced by Lactic Acid Bacteria (LAB) and, at a minor level, Acetic Acid Bacteria (AAB).

Thousands of species and species of acid bacteria and wild yeasts could be cultivated in a sourdough starter.

The balance of the prominent strains provides the level and type of acidity.

By changing the flour, the feeding ratio and the environment, we can alter the flavour and smell of a starter.

Features of lactic acid

Lactic acid has a mature sour flavour with a creamy linger. Lactic Acid Bacteria (LAB) produce lactic acids as they ferment the sugars in the dough.

Features of acetic acid

Acetic acid is the sharp, vinegary twang that attacks the taste buds.

Vinegar is diluted acetic acid. The famous sourdoughs of San Francisco taste heavily of acetic acid.

It is also produced by LAB when sugars follow an alternative fermentation pathway. When LAB utilises this route, carbon dioxide gas can also be produced.

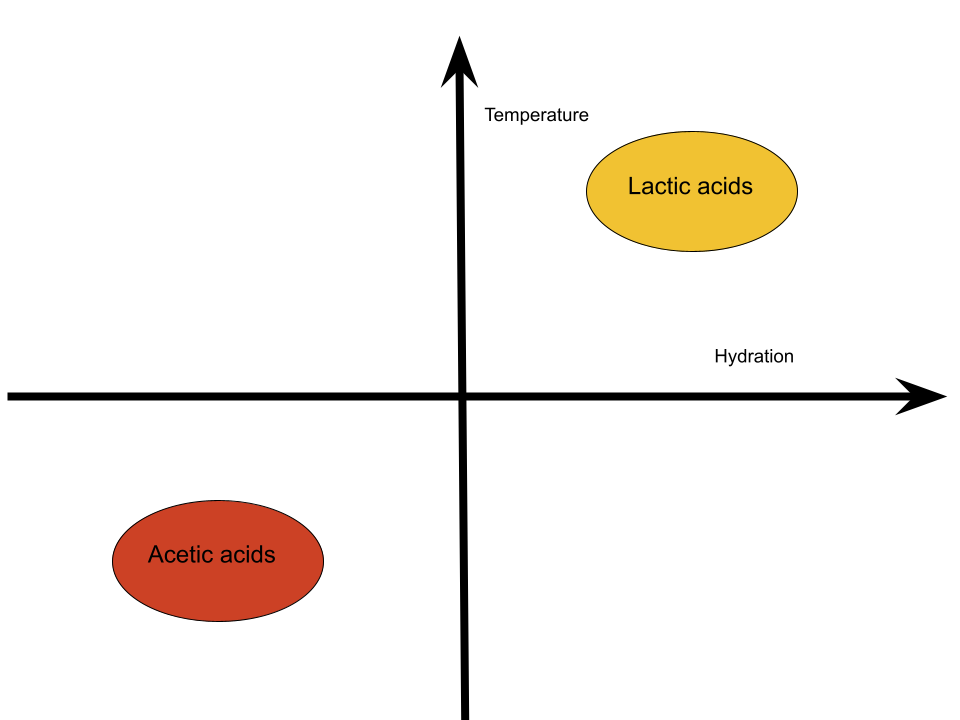

How To Tweak The Ratio Of Lactic To Acetic Acids In Sourdough

If you want to change the levels of lactic acid or acetic acid in your bread, there are various routes.

The best thing to do is to change the starter’s temperature or viscosity.

Here’s how it works:

When LAB ferments in ideal conditions, it prefers to utilise homofermentative lactic bacteria, thus solely producing lactic acid.

Heterofermentive bacteria produce both acetic and lactic acid. Both types of LAB increase activity in warmer environments; however, homofermentative bacteria ferment at a much faster rate at higher temperatures.

When colder, it’s common for heterofermentative bacteria to be more active than homofermentative, creating more acetic acids.

More lactic acid = 30-35C (86-95F)

More acetic acid = 20-25C (68-77F)

There is less free water when a starter’s consistency is thick and dense. Water is used in fermentation as a carrier between cells. This means that in a dense starter, fermentation is slower than a runny one. The slower rising rate leads to acetic acid being the prevailing acid.

NOTE: Don’t expect immediate results. Over time, a starter will become more and more complex as it becomes efficient at tackling the fresh bacteria. It requires regular and consistent treatment to transform the ecosystem.

How To Make Sourdough Bread More Sour

Once you’ve got your starter-smelling sourer, you’ll be itching to get baking.

Here’s how to tweak your sourdough bread recipe to make sour bread:

Use plenty of Starter for Extra Tangy Sourdough Bread

To increase the sourness of sourdough bread, we want to add as many acid-producing bacteria as possible. This means using more starter than average will produce a more sour-tasting bread.

Use 30-50% of sour starter to make your bread more acidic. Lower the amount of starter to 10-15% to lower the sourness.

TIP: If your starter is low in acidity, you can use an extended autolyse with the starter, but without salt. The autolyse increases leavening activity.

Use the same flour that’s in your starter

Over time, the enzymes in the starter adapt to consume the flour’s bacteria.

So, if the same flour is used to make bread, the starter will be more efficient at breaking it down, improving its ability to produce more acids.

Note: Pentosans found in rye flour retain water. This makes bread moister and remains fresh for longer.

Bulk ferment for longer for more sour flavour

The more dough develops, the more flavour will be imparted through organic acid activity.

Push the rise during bulk fermentation and proofing for as long as possible to let the acids develop. A great way to do this is by using the fridge.

Enzymatic reactions slow down in cold temperatures. However, dough stored in the fridge will continue to undergo hydrolysis, the natural breakdown of starch in water.

Placing the dough in refrigeration at the start of bulk fermentation provides a plethora of simple sugars for the yeast and acid bacteria to use for fermentation later on.

If you choose to extend bulk fermentation time by placing your dough in the fridge, you need to be careful about oxidation.

The longer dough is exposed to oxygen, the weaker and less flavourful it becomes.

Kneading time should be reduced and replaced by a gentle mix and stretch and folds throughout the first rise.

Note: Longer proofs make sweeter sourdough bread as more complex starches will deteriorate into simple sugars. The extra sweetnes can overpower bitterness, meaning the bread will be acidic but won’t taste as sour.

Place your proofed dough in the fridge

This is one of the best tips!

Using the same science that increases acidity in a starter when it’s left to sit at the peak of its rise. Extract more sour flavours from our bread dough by doing the same in the proofing process.

Put your sourdough bread in the fridge when it is around 75% proofed to slow down the rise.

The dough will sit at the peak of its rise (fully risen) for a couple of hours, developing extra acids!

NOTE: The fridge final rise provides many of the key features of San Francisco sourdough. Its world-renowned blisters and mighty sour, yet sweet flavour are due to the local environment and fridge-proofing.

Add an acidic ingredient

Although I recommended no further additions, you can add acidic ingredients to your dough recipe for an extra hit.

Citric acid is also known to bakers as sour salt. It will make your bread sour. Add around ⅛th of a teaspoon per loaf.

Vinegar is diluted acidic acid; adding it will make your bread more sour.

Vinegar also has many other benefits in bread dough.

Lemon juice adds acidity as it contains around 8% citric acid. It can be used to make bread sour, but sparingly, as the flavour of lemon can be overpowering.

Ending Thoughts On Making Sourdough More Sour

Now you have the science behind a sour starter, I hope you are itching to make your starter more to your taste!

Always, avoid making too many changes at the same time. You don’t need to follow all of these tips to enjoy a sour starter. Just one or two can make a difference!

To learn more about sourdough fermentation, click the link. Please share with me your success stories in the comments below, or ask any questions.

Sour sourdough frequently asked questions

If you’ve enjoyed this article and wish to treat me to a coffee, you can by following the link below – Thanks x

Hi, I’m Gareth Busby, a baking coach, senior baker and bread-baking fanatic! My aim is to use science, techniques and 15 years of baking experience to make you a better baker.

Table of Contents

Related Recipes

Related Articles

Latest Articles

Baking Categories

Disclaimer

Address

53 Greystone Avenue

Worthing

West Sussex

BN13 1LR

UK